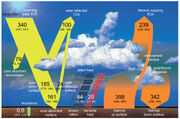

Figure 2.11 Global mean energy budget under present-day climate conditions. Numbers state magnitudes of the individual energy fluxes in W m–2, adjusted within their uncertainty ranges to close the energy budgets. Numbers in parentheses attached to the energy fluxes cover the range of values in line with observational constraints. (Adapted from Wild et al., 2013.)

Since AR4, knowledge on the magnitude of the radiative energy fluxes in the climate system has improved, requiring an update of the global annual mean energy balance diagram (Figure 2.11). Energy exchanges between Sun, Earth and Space are observed from space-borne platlat-forms such as the Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES, Wielicki et al., 1996) and the Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE, Kopp and Lawrence, 2005) which began data collection in 2000 and 2003, respectively. The total solar irradiance (TSI) incident at the TOA is now much better known, with the SORCE Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM) instrument reporting uncertainties as low as 0.035%, compared to 0.1% for other TSI instruments (Kopp et al., 2005). During the the 2008 solar minimum, SORCE/TIM observed a solar irradiance of 1360.8 ± 0.5 W/m–2 compared to 1365.5 ± 1.3 W m–2 for instruments launched prior to SORCE and still operating in 2008 (Section 8.4.1.1). Kopp and Lean (2011) conclude that the SORCE/TIM value of TSI is the most credible value because it is validated by a National Institute of Standards and Technology calibrated cryogenic radiometer. This revised TSI estimate corresponds to a solar irradiance close to 340 W m–2 globally averaged over the Earth’s sphere (Figure 2.11).

The estimate for the reflected solar radiation of the TOA in Figure 2.11, 100 W m-2, is a rounded value based on the CERES Energy Balanced Filled (EBAF) satellite data product (Loeb et al., 2009, 2012b) for the period 2001-2010. This data set adjusts the solar and thermal TOA fluxes within their range of uncertainty to be consistent with independed estimates of the global heating rate based on in situ ocean observations (Loeb et al., 2012b). This leaves 240 W m-2 of solar radiation absorbed by the Earth, which is nearly balanced by thermal emissions to space of about 293 W m-2 (base on CERES EBAF), considering a global heat storage of 0.6W m-2 (imbalance term in Figure 2.11) base on Argo data from 2005 to 2010 (Hansen et al., 2011; Loeb et al., 2012b; Box 3.1). The stated uncertainty in the solar reflected TOA fluxes from CERES due to uncertainty in absolute calibration alone is about 2% (2-sigma), or equivalently 2 W m-2 (Loeb et al., 2009). The uncertainty of the outgoing thermal flux at the TOA as measured by CERES due to calibration is 3.7 W m-2 (2 <sigma>). In addition to this, there is uncertainty in removing the influence of instrument spectral response on measured radiance, in radiance-to-flux conversion, and in time-space averaging, which adds up to another 1 W m-2 (Loeb et al. 2009).

The components of the radiation budget at the surface are generally more uncertain than their counterparts at the TOA because they canoot be directly measured by passive satellite sensors and surface measurements are not always regionally or globally representative. Since AR4, new estimates for the downward thermal infrared (IR) radiation at the surface have been established that incorporate critical information on cloud base heights from space-borne radar and lidar instruments (L'Ecuyer et al., 2008; Stephens et al., 2012a; Kato et all., 2013). In line with studies based on direct surface radiation measurements (Wild et al., 1998, 2013) these studies propose higher values of global mean downward thermal radiation than presented in previous IPCC assessments and typically found in climate models, exceeding 340 W m-2 (Figure 2.11). This aligns with the downward thermal radiation in the ERA-Interim and ERA-40 reanalyses (Box 2.3), of 341 and 344 W m-2, respectively (Berrisford et al., 2011). Estimates of global mean downward thermal radiation compute as residual of the other terms of the surface energy budget (Kiehl and Trenberth, 1997; Trenberth et al., 2009) are lower (324 to 333 W m-2), highlighting remaining uncertainties in estimates of both radiative and non-radiative components of the surface energy budget.

Estimates of absorbed solar radiation at the Earth's surface include considerable uncertainty. Published global mean values inferred from satellite retrievals, reanalyses and climate models range from bellow 160 W m-2 to above 170 W m-2. Recent studies taking into account surface observations as well as updated spectroscopic parameters and continuum absorption for wator vapor values towards the lower bound of this range, near 160 W m-2, and an atmospheric solar absorption around 80 W m-2) (Figure 2.11) (Kim and Ramanathan, 2008; Trenberth et al., 2009; Kim and Ramanathan, 2012; Treberth and Fasullo, 2012b; Wild et al., 2013). The ERA-Interim and ERA-40 reanalyses further support an atmospheric solar absorption of this magnitude (Berrisford et al., 2011). Latest satellite-derived estimates constrained by CERES now also come close to these values (Kato et al., in press). Recent independently derived surface radiation estimates favour therefore a global mean surface absorbed solar flux near 160 W m-2 and a dowward thermal flux slightly above 340 W m-2 respectively (Figure 2.11).

The global mean latent heat flux is required to exceed 80 W m-2 to close the surface energy balance in Figure 2.11, and comes close to the 85 W m-2 considered as upper limit by Trenberth and Fasullo (2012b) in view of current uncertainties in precipitation retrieval in the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP, Adler et al., 2012) (the latent heat flux corresponds to the energy equivalent of evaporation, which globally equals precipitation estimates). This upper limit has recently been challenged by Stephens et al. (2012b). The emerging debate reflects potential remaining deficiences in the quantification of the radiative and non-radiative energy balance components and associated of the radiative and non-radaitive energy balance components and associated uncertainty ranges, as well as in the consistent representation of the global mean energy and water budgets (Stephens et al., 2012b; Trenberth and Fasullo, 2012b; Wild et al., 2013). Relative uncertainty in the globally averaged sensible heat flux estimate remains high owing to the very limited direct observational constraints (Trenberth et al., 2009; Stephens et al., 2012b).

In summary, newly available observations from both space-borne and surface-based platforms allow a better quantification of the Global Energy Budget, even though notable uncertainties remain, particularly in the estimation of the non-radiative surface energy balance components.